Nailya Alexander Gallery is pleased to announce Boris Ignatovich: Master of Russian Avant-Garde Photography presented in collaboration with the Boris Ignatovich Estate, Moscow. This is the first ever solo exhibition held in New York for Boris Ignatovich (1899-1976), a towering figure in Russian Constructivist photography. The exhibition features some of the artist’s most celebrated photographs from the 1920s and 1930s, including large-scale gelatin silver prints of unprecedented size (29 x 39 inches) made by Ignatovich himself for the 1969 exhibition at the Moscow Central House of Journalists in honor of his seventieth birthday. We are privileged to exhibit these one-of-a-kind art objects in the gallery for the first time in nearly fifty years.

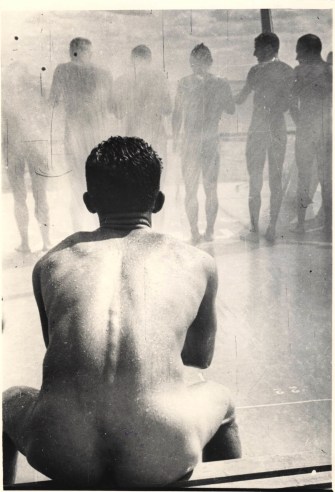

The history of Russian art cannot be imagined without Ignatovich, a great innovator, who left an indelible mark on the evolution of early Soviet experimental photography, and reformed reportage with startling perspectives and artistic expressiveness. Ignatovich worked under the philosophy that his work should not only reflect the life and culture of the Soviet Union, but actively shape it. His bold compositions, rich lighting contrasts, and striking insights capture new industry, architecture, working people and daily life during a turbulent period. “The revolution in Russia swept away the bourgeois order and the bourgeois aesthetic,” writes historian of Russian photography Valery Stigneev. “The builders of a new society needed their own language and idols. On this great, fast-moving wave of art rose Mayakovsky, Rodchenko, Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Deineka, El Lissitsky, and others. More accurately, they made this Art. Boris Ignatovich made Photography.”

Ignatovich took his first reportage photograph in 1923 with a pocket kodak camera capturing the Soviet writer Mikhail Zoshchenko buying apples near the Smekhach office (humor magazine he worked at the time). By 1927 he became a picture editor for the famous newspaper Bednota, also contributing photographs to the publication about changes happening in both urban and rural life.

Two years later, he joined the famous October group, an avant-garde union of artists, architects, film directors, and photographers, many of whose members — including Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and El Lissitzky — used Ignatovich’s images in their photomontages and designs. When Rodchenko was expelled in 1930, Ignatovich replaced him as head of the photographic section until the group’s dissolution in 1932. Ignatovich remained faithful to photographic experimentation for the entirety of his career. He advocated for collectivism in photojournalism at the Soyuzfoto agency, where photographers working under him formed the so-called “Ignatovich Brigade,” and spoke out openly against the Soviet Union’s tightening grip on artistic expression. He contributed to the publications USSR in Construction, Krasnaya Niva, Ogonyok, Soviet Photo, and Pravda, among others, and worked as a cameraman on documentary films, including one of the first sound films, Olympiada of the Arts. For a special 1931 edition of USSR in Construction, he shot some of the first aerial photos of St. Petersburg from an R-5 reconnaissance plane that flew perilously close to the city’s landmarks. Ignatovich served as chairman of the Moscow Association of Photojournalists in 1932, and during his life saw his work exhibited widely not only in Russia but also across Western Europe.

"Boris Ignatovich was a universal photographer,” writes Aleksandr Lavrentiev, art historian and director of the Rodchenko-Stepanova Archive. “He was a journalist and a reporter, a war photographer, a portraitist, a pedagogue, and a master of applied photography. Ignatovich's own prints were unrepeatable artworks of his darkroom...The tonal richness of Ignatovich's prints is akin to painting. He turned photographs into art, because he understood what art is. But he was not imitating painting. It all flowed from his technique, from what he’d seen, from mastery.”